Simple arithmetic addition with neural networks

Published July 17, 2019

Before we start, I want to clarify that I am not just some neural network script kiddie, and that my blog is not going to be just a personal log of all the neural networks I make. I also enjoy electronics and hardware design. That being said, check out this neural network I made!

There is an underlying perception that people new to the topic of machine learning have, and that is this: when a model isn't doing too hot, you need either more data or more hidden layers with more neurons between them. This misconception isn't their fault; it seems everyone in the news is talking about these huge neural networks trained on terabytes of data to decide whether to advertise an eco-friendly backpack or water bottle to an unsuspecting consumer based on their heart rate variance. However, more neurons != better fit, as I will proceed to show.

We often think of neural networks as endlessly flexible tools. I mean, can't they approximate any known function? And while that is mathematically proven to be true, you, as a real-world practitioner of ML, have to consider how much more complicated the cost function gets for every single neuron you add. The already-bumpy landscape of a 3D cost function becomes more wrinkly, and your model has a much higher chance of getting stuck in a local minima.

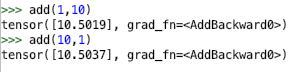

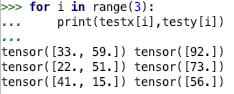

This becomes apparent when you train a neural network to do something as simple as addition. I generated 1000 examples of addition of two integers between 0-100, which looks like this

Model A

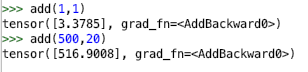

Using these, I trained a simple neural network with no hidden layers (does that invalidate it as a neural network? I'm not sure the semantics of the name), 2 input nodes, and 1 output node. Let's call it Model A. Here's the results

As you can see, this model is a little off, but asymptotically correct. The error is nearly constant regardless of the inputs, meaning as the inputs go up, the total percentage error of the model goes to 0. In addition, this model only requires 2 multiplications and 2 additions to perform one addition, which is only a 4x cost computationally. Since our computers are definitely more than 4x faster than they were when addition was invented, this model is feasible for use in modern industry.

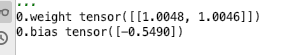

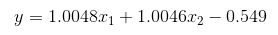

Even better, this example of machine learning is explainable. If we take a look at the weights, we can boil this neural network down into one equation. Using x1 and x2 as the first and second inputs respectively, our neural network's weights can be algebraically expressed.

Becomes

Becomes

This AI model is clearly understandable by any person who knows basic algebra, and therefore can be trusted to perform addition in a transparent method that doesn't involve plotting to kill its human creators with some of its spare neurons.

Model B

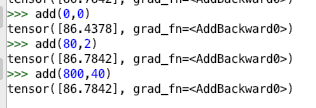

Now, contrast this simple but effective Model A with a second, more complex Model B. This model has a hidden layer with one neuron in it, in addition to the input 2 nodes and output node. As such, it performs worse addition.

We see that the error is significant, definitely not enough to just round away like we could with Model A. This model also took extra time to train, since it had an additional 3 equations to calculate. It is significantly less feasible for use in industry because of its inefficiency and inaccuracy.

Model C

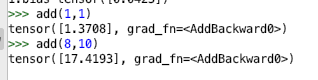

"But what about huge inner layers Andy? You're just using one! Won't that solve all our problems like Elon Musk and Andrew Ng promised?" NO! Here I've created Model C, which has 10 hidden neurons in its hidden layer.

It's AWFUL! Terrible! Abysmal! A child could do better than that! Whe- oh, we're getting a message from ML themselves. They said to change the learning rate. Whoops. Here's the actual results

We can see that though Model C performs better than Model B's small hidden layer, it's doesn't even beat Model A, the simplest model of them all. And additionally, the computation cost is through the roof! Definitely not scalable for industry.

The takeaway of this is that not all machine learning problems can be solved by throwing tons of neurons at them, in the same way that not all real world problems can be solved by throwing tons of ninjas at them (but most of them could). So before you jam 16 fully-connected hidden layers of 256 neurons each in your neural network, think about how complex the function you're trying to model actually is. And pick a model that fits the function you need, instead of one that fits your mental model of how chunky thicc a SOTA neural network should be. You might get better results for less computation.

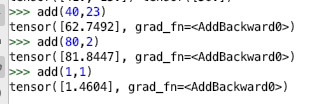

Bonus: Addition using any of these models is not commutative, which was really funny to me. I think this has applications for curing the boredom once mathematicians and kindergarteners get tired of adding 1 and 1 together. They can now do it in new ways!