Electronics Teardown: Stelo CGM

Published October 6, 2024

Hello everyone,

Hope everything is well in your life. I'm working on my implants talk for Hackaday Supercon (more info here). As part of my research, I tried out the Stelo CGM by Dexcom, this is (I think) the first over-the-counter continuous glucose monitor. I'll tell you how it was and then we're gonna dissect this bad boy!

How did it feel?

In a world where glucose monitors are >100$ on Amazon sans insurance, Dexcom offers an affordable ($50) CGM with easily accessible data export, sampling your blood sugar every 5m and passing it to your phone via Bluetooth. The device lasts 15.5 days and comes in a kit of two, meaning annual glucose tracking can now be accomplished for ~1k USD.

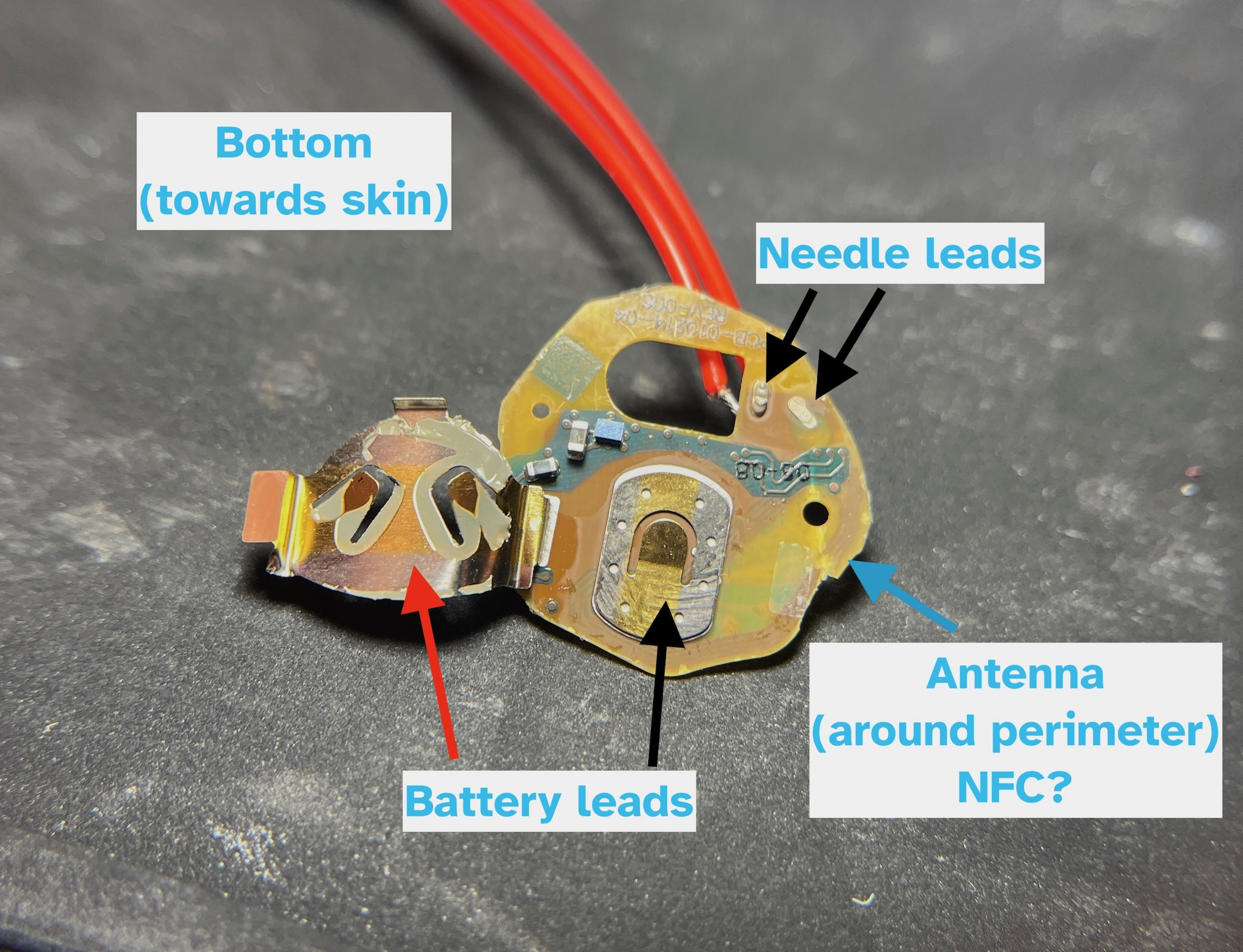

Deploying is done through this spring-loaded applicator, and is easy as pressing a button. A sharp, stiff needle in the cap punches a small hole in your arm and retracts, leaving behind the sensor body and a flexible needle with glucose oxidase coating. 15 days later, the app sends you an alert to replace it, and 12 hours after that it stops recording data.

When I got this notification I went and got my teardown tools ready — nothing excites me more than opening a black box!

Internal pics

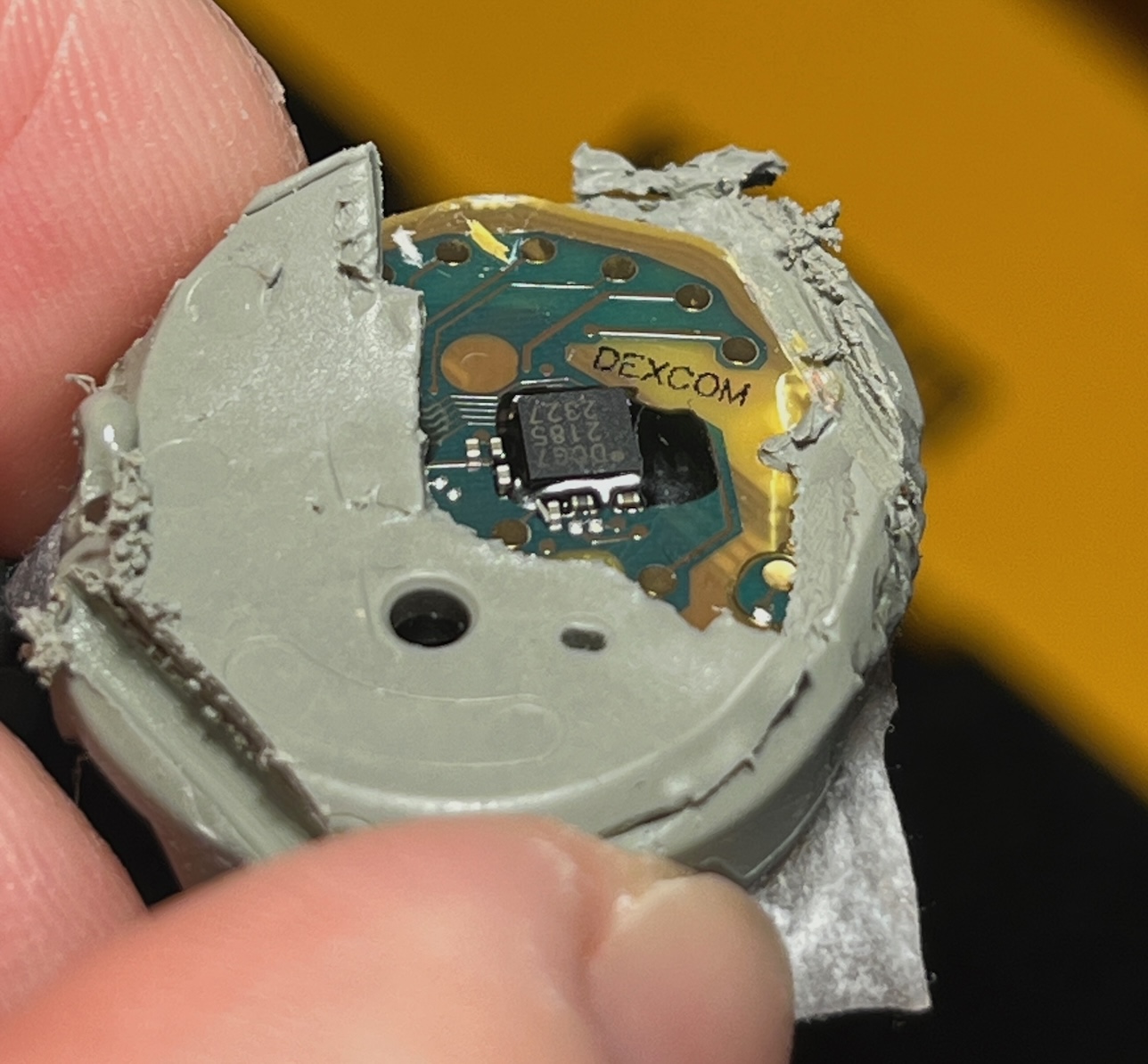

I started out using a Dremel, but then realized the soft rubber casing is weak enough you can just use wire snippers. The board is quite thin and liable to break as you peel the rubber off, so I had to be careful.

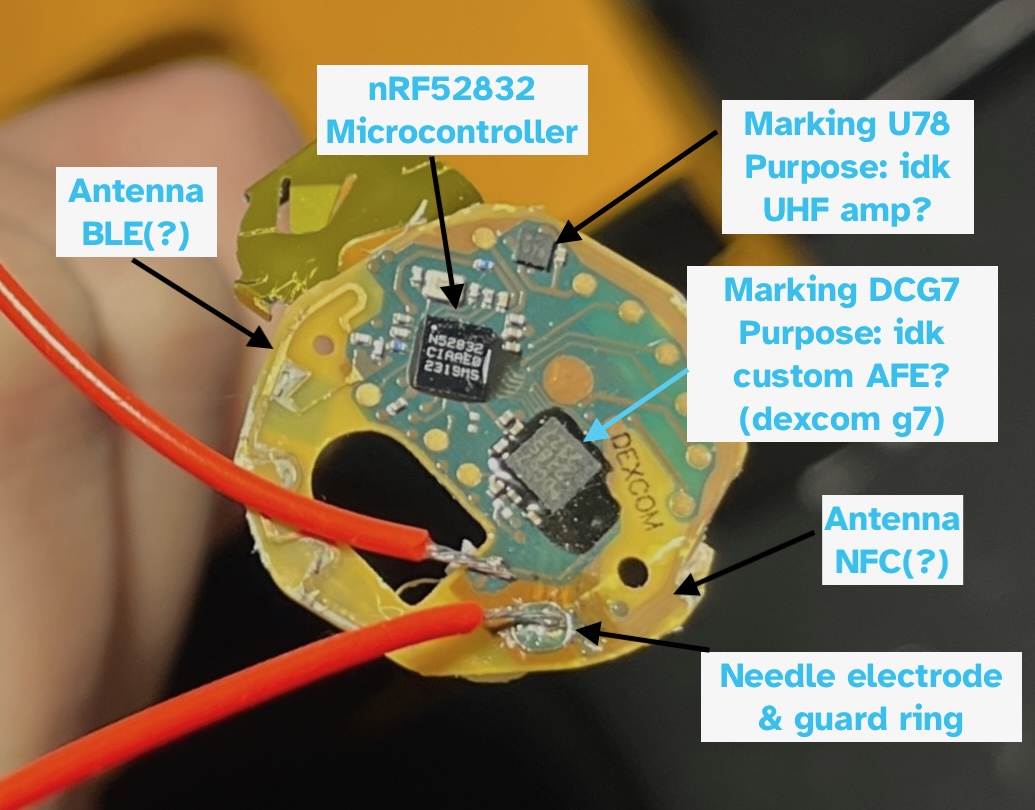

Broad architecture

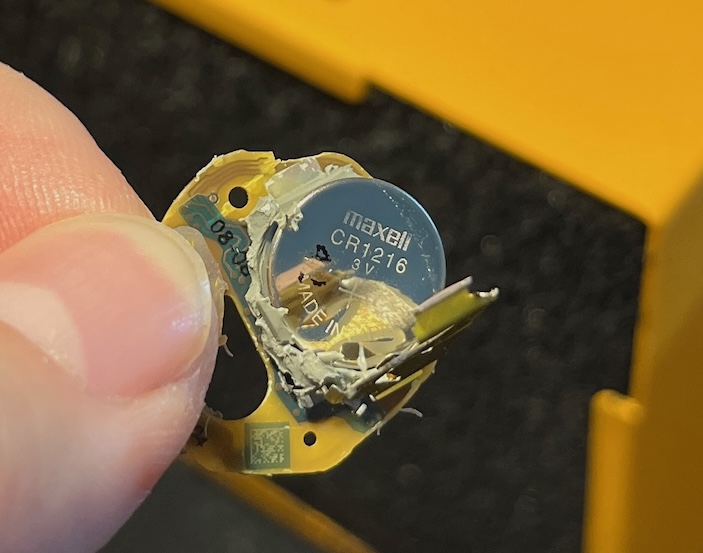

As far as I can tell, the glucose oxidase on the needle reacts with interstital glucose levels, turning your glucose concentration into a voltage. The Stelo uses an nRF52832 microcontroller to record this, waking up every 30 seconds to read the sensor and every 5 minutes to transmit the data to your phone/watch. The whole thing is powered by a coin cell battery, the Maxell CR1216 (datasheet), which claims a 25mAh capacity

Question 1 — are we getting scammed on lifetime?

One of the things I wanted to find out through this teardown was if the battery life was longer than the software claimed. 15 days is an incredibly square number, which led me to believe that Dexcom is "guaranteeing performance" by imposing an artificial software lifetime limit when the sensor could really go for longer.

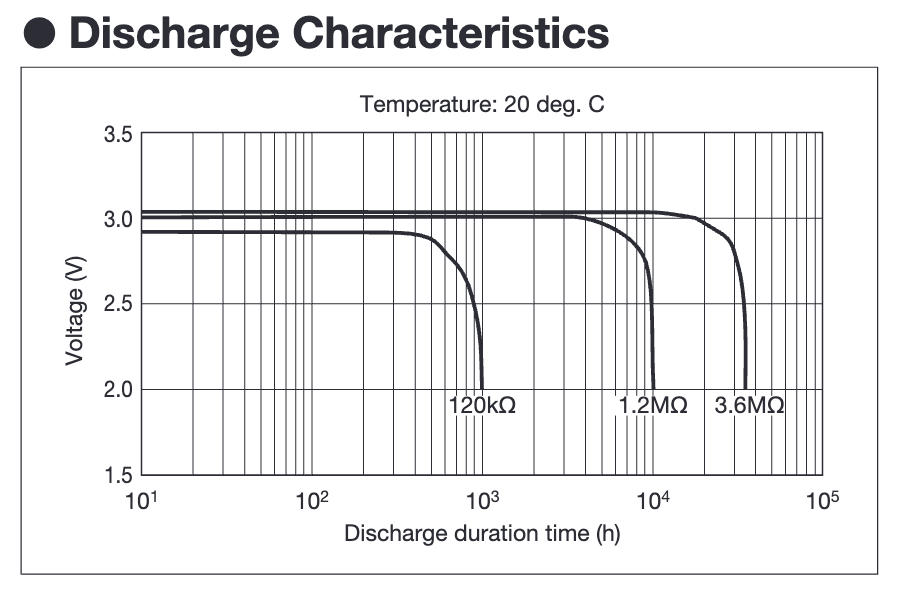

Immediately after I took the sensor off, the battery still reads 2.95V, but since this battery sports an extraordinarily flat discharge curve I have little idea how much capacity is left.

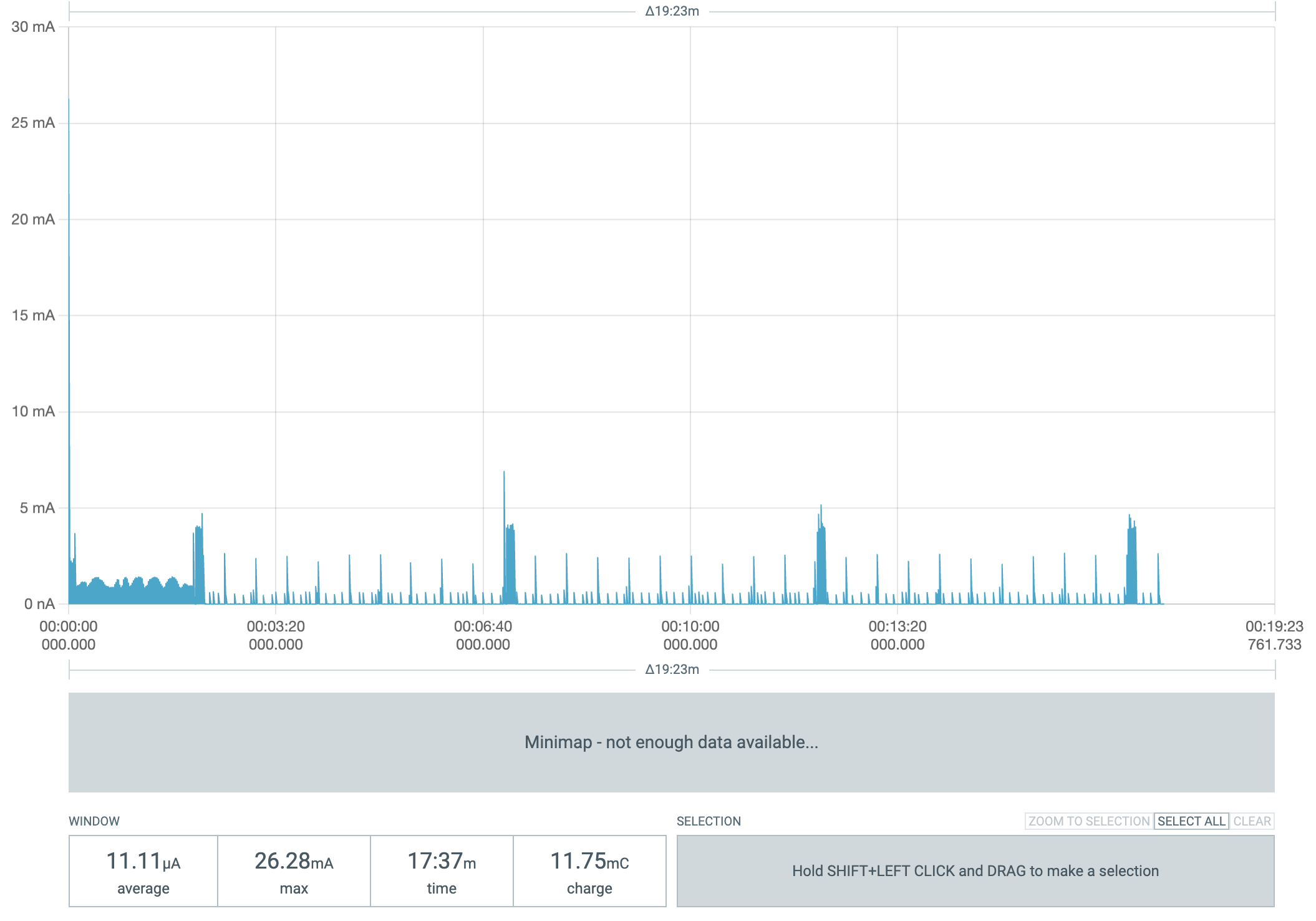

Since we can't tell by looking at the voltage, I powered the device using an external meter (Nordic PPK2) to find out how much power it draws. Here's the current consumption over 15 minutes:

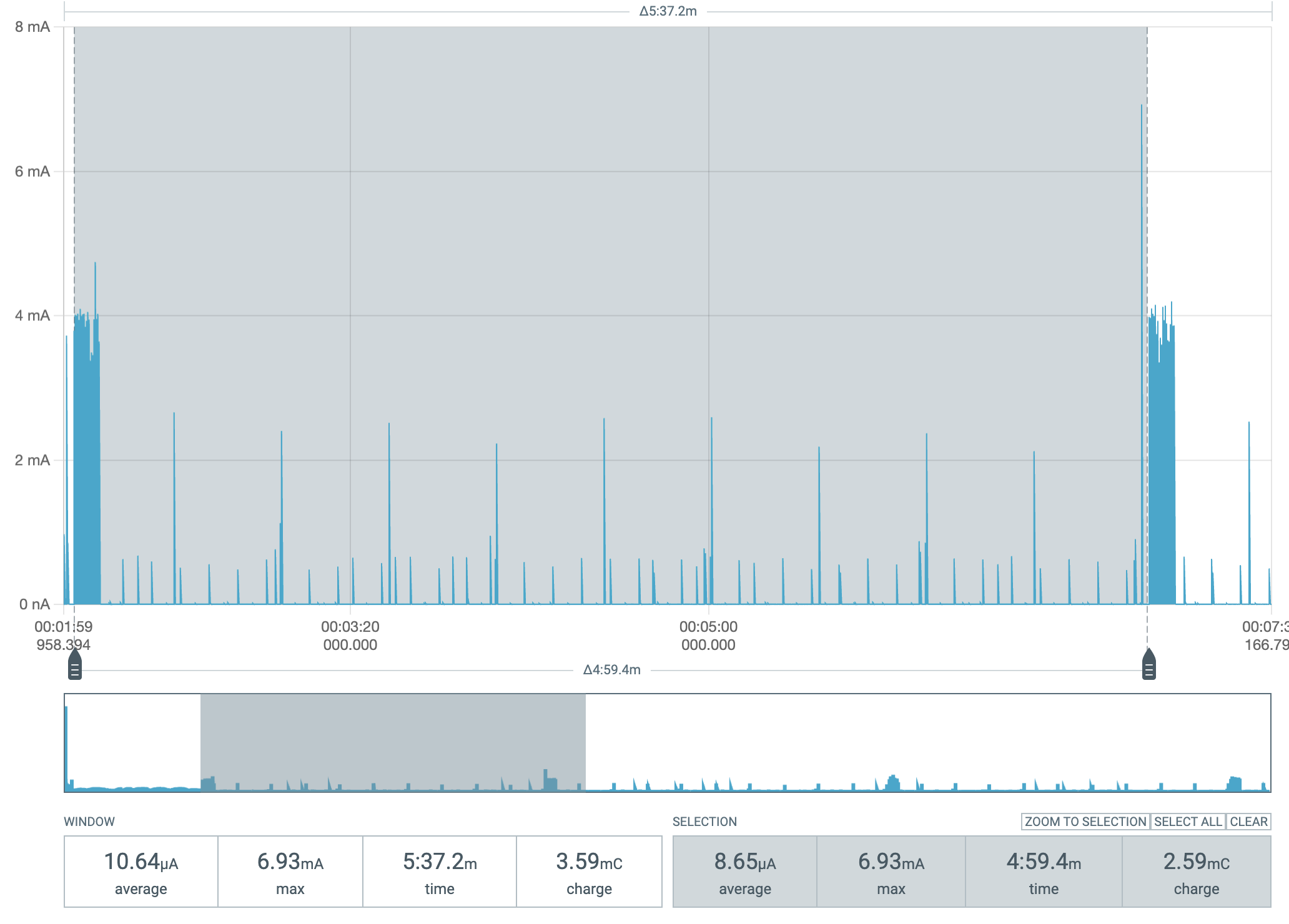

After an initially high power boot for ~2 minutes, we reach steady operating conditions. Small spikes happen every 7.5 seconds, medium spikes every 30 seconds, and then large bursts of activity every 5 minutes denote Bluetooth activity (large bars on the ends). Average power consumption during steady-state is 8.7uA. If you'd like to see this power consumption data more granularly, feel free to email me for it.

Given its capacity of 25mAh, the battery on the Stelo could theoretically run it for 17 weeks continuously. However, nominal capacity assumes discharge down to 2V — while the nRF52832 microcontroller keeps working down to 1.7V, the other chips on this board may not. Let's say the board needs >2.8V, then we can model our 8.7uA draw as a ~300kΩ load. On the battery curve given above, this corresponds to a lifetime of ~1000 hours, or about 5 weeks. Adding some margin for safety, we may indeed arrive at a reasonable lifetime of 15 days for this device.

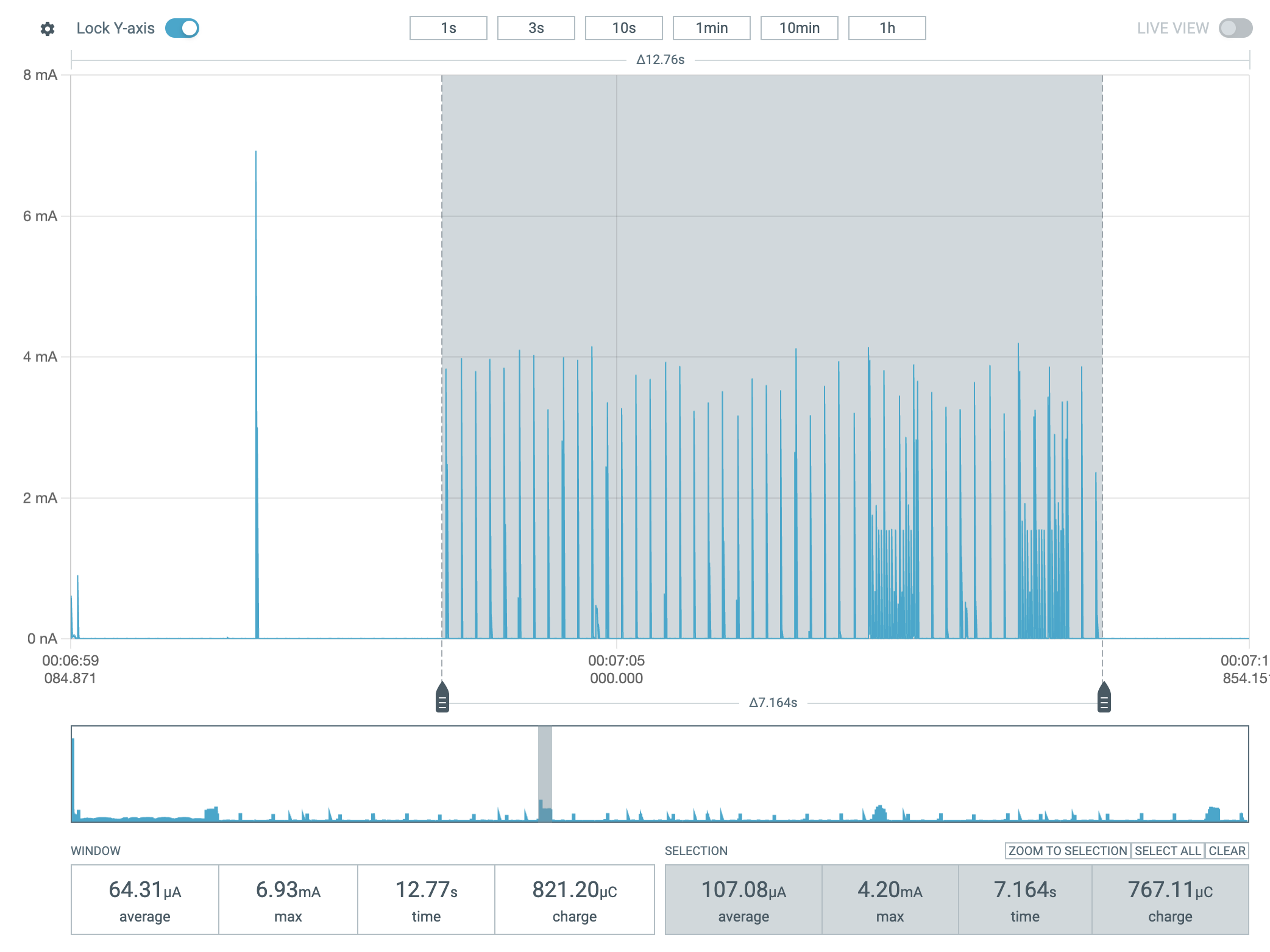

Oh also, here's what the power looks like during the Bluetooth transmission. It looks like >50 packets, and averages 100uA for 7 seconds.

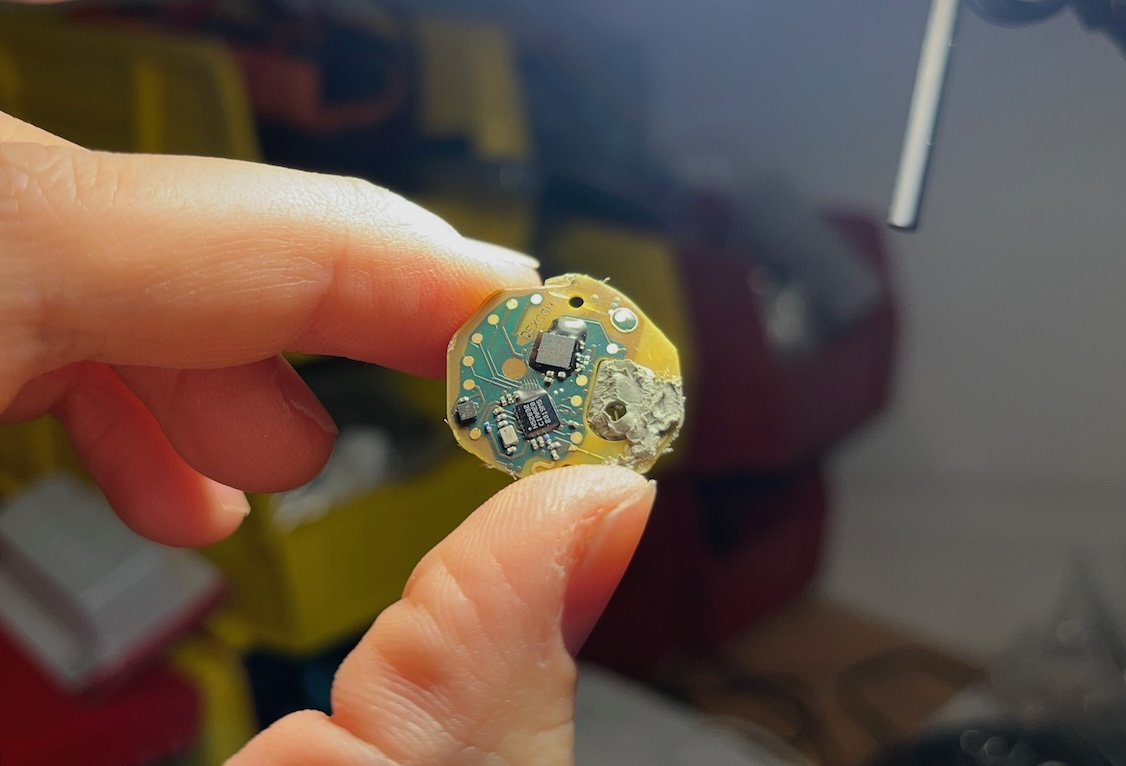

Question 2: What other chips are in this thing?

The nRF is easily identified, but I cannot figure out what the other two are. The top has a small IC which seems to be connected to the larger antenna (possibly RFID?), and when I look up U78 it turns up an UHF amplifier (possible) with a different package, the 3SK206. But UHF antennas are pretty big usually, at least bigger than the Bluetooth one.

The other big chip might be an analog frontend for the glucose needle electrode (the traces for that go right towards it). If so, it's amplifying the readout voltage from the glucose sensor before being digitized by the nRF, but again I could not figure out the specific part. Closest part marking I could find was a step-up converter, but that doesn't seem likely.

Question 3: What's the BOM?

I'm pretty interested in this, just because I like knowing internal info about consumer products. But until I figure out the other chips, I can't really give a good estimate for cost. I also have no idea what the encasement or needle or assembly cost, and the app is pretty nice too and that can't be easily included in cost of the product. The stuff I do know: the nRF costs about 2-3$ in bulk, passives I can't imagine exceed 50 cents in total, and the board is likely under 1$. I'm not too bummed by cost however, since in France the Libre Freestyle 2 is 40 Euro and I can't imagine them making much money over there.

Conclusion

Knowing that the total power consumption is 8.7uA at 3V (~30uW) I think we can power this device using energy harvesting. For reference, I've seen a 4cm^2 solar panel receive nearly 3 mW in direct sunlight. Imagine a permanent CGM, powered simply by going outside in the sun for 15 minutes a day. What a life!