Paper Delivery: Sinusoidal Skin Displacements

Published June 22, 2021

I've been reading a ton of research about how our touch receptors work. You may think it's simple, and it's not. I'm gonna show y'all a seminal paper on how our nerves react to mechanical sensation. When they dropped this supa hot fire in 1982, it inspired a lot of research which underlies our current understanding of how our brain processes touch.

They're made of meat

Quick recap: there's 4 mechanoreceptors in our skin, and they each detect something different; low and high frequency vibrations, pressure, and skin stretching. Each receptor is a special structure specially designed to release ions in response to a very narrow kind of stimulus.

Each receptor is attached to a nerve cell, and triggers action potentials in the nerve only when their stimulus occurs. The stronger the stimulus, the faster the receptor dumps ions onto the nerve, and the more often their action potentials get fired.

These nerves follow a direct path to the brain, and each nerve gets its own "column"-ish of brain cells that receive and process its impulses. So when someone touches your finger, they are firing neurons in on particular, consistent location on your brain's surface. This is how our brains know where we were touched.

But how do our brains know what we touched? How do our neurons interpret that chain of action potentials from the hand's receptors into the sensation of touching fabric, or holding a wooden block?

Is this a response from touching a cat, or a dog? Your brain knows, even if you might not!

Old news

Because the fire rate was the most obvious change in response to stronger stimulus, scientists used to think that the neurons talked to each other using average firing frequency. This is called a rate code.

However, this hypothesis is being challenged today. The brain can react to certain stimulus faster than it takes for a receptor to fire twice, for instance in reflexes. Since the neuron needs at least two firings to determine a "rate", researchers guess that there must be some other information present in a single firing spike besides just how many there are.

Though they don't really talk about neural coding at all, the paper "Responses of Mechanoreceptive Afferent Units in the Glabrous Skin of the Human Hand to Sinusoidal Skin Displacements" offers a compelling reason to discard the rate code hypothesis.

Paper's Setup

Research papers always take a long time to get to the point. In this paper, they poked a plastic rod into a participant's skin, directly over one of the four mechanoreceptors.

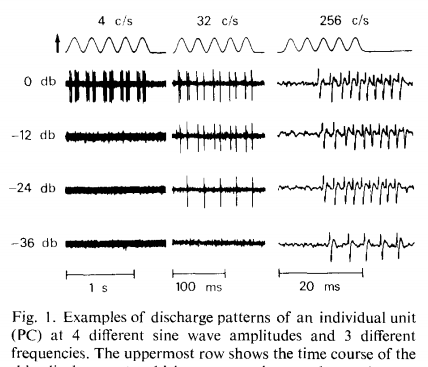

They modulated the rod in a sinusoid, and kept halving its total movement length, starting at 1mm and stopping at 0.125mm peak-to-peak total travel. 1mm is considered 0dB, 0.5mm is -6dB, and so on.

Sinusoidal stimulus used to move the rod, and the action potentials produced

The rod was moved for 5 periods of a sinusoid, at a bunch of different frequencies (powers of 2 from 0.5 to 256Hz, then also one at 400Hz).

How'd they find these mechanoreceptors anyway? They used something called microneurography, or "stab tiny needle into the nerve repeatedly until you only see one mechanoreceptor spiking when we poke the victim's hand with a stiff hair". Kinda cool that our body just works like that, and we can exploit it so well.

Graphs please?

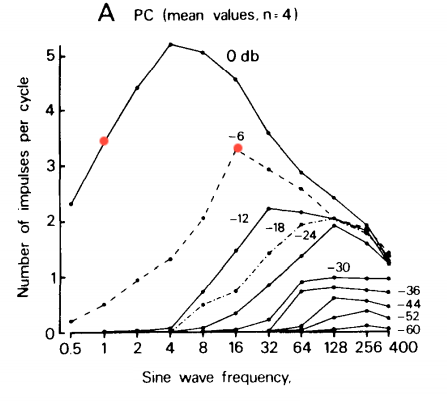

Alright, alright! Here's the averaged responses for the PC, or Pacinian corpuscle. These are egg-shaped receptors that sense high frequency vibrations. The field typically uses 1 impulse/stimulus as a breakpoint to indicate the active range of a mechanoreceptor. For the PCs at full amplitude, they are all-sensitive.

Responses per sinusoidal period for all recorded Pacinians

This graph is what provides the really good reason against the rate coding hypothesis. Consider the 0dB line for 1Hz and the -6dB for 16Hz (marked in orange). The firing rates are nearly the same, yet we can clearly tell the difference between a 1Hz and 16Hz movement!

Clearly, there is a little more going on than simple rate coding.

If Not Rate, What Else?

Current researchers are looking into using relative lag between first firing times from a local group or "population" of mechanoreceptors. Relative latency was used in 2008 in a salamander retina with great success:

In a 2008 paper, researchers measured a salamander's eye to see how retina cells encoded dark vs bright light when they talked to the brain. Instead of spike count or firing rate, ganglions changed their activation time relative to other ganglions near them. pic.twitter.com/9mh86s6cwi

— Andy (@oldestasian) June 22, 2021

Other peeps are using the interspike period, or burst gap, or silent gap between series of nerve firings from a single nerve to determine the frequency of vibration or texture that's being touched.

I think it's some combination of latency across multiple populations, and maybe the number of spikes being sent. But what do I know? Just that there's a lot more to learn about one of our most foundational senses! Cya later!