Spin Tank Proof-of-Concept Test

Published August 20, 2019

The problem with modern day tank armor is that it relies too heavily on brute strength for defense. Armor can be made to actively resist attacks by means of a light, rapidly rotating hull that deflects projectiles instead of the heavy armor plates used today that simply endure every hit thrown at them.

Modern tanks suck

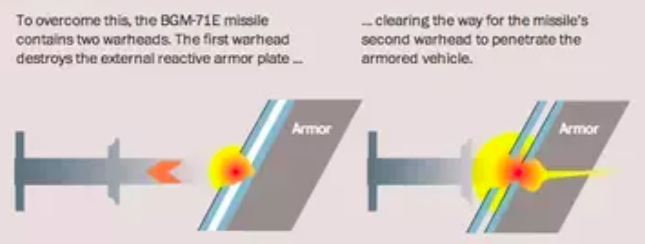

Tank armor must be strong enough to resist small arms fire (rifles, pistols, submachine guns) and stronger, penetrating projectiles (anti-tank missiles, SAMs). Thick depleted uranium plating forms the outer shell, and sheds small arms fire like water. This plating, in conjunction with ceramic armor and air pockets, also allows tank armor to redirect the focused explosions of anti-tank missiles. Anti-tank missiles first contact the tank, then use shaped charges to shoot a thin, fast-moving jet of plasma at the hull to melt a deep hole into the cockpit. On a normal tank, this stream goes straight the armor and must be redirected by the aforementioned air pockets to avoid injuring the crew.

Not only is this armor dumb (not reactive), it is also super heavy because it takes every impact head-on. I couldn't find definitive stats on the armor weight, but it's designed to be thick and expendable. All these factors make the tank less manouverable than it could be, and more expensive than necessary. This doesn't have to be the case.

Spin tank

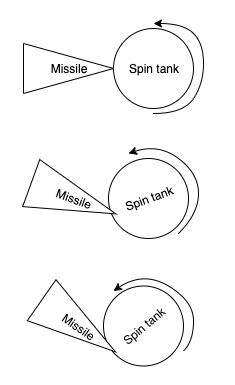

What if instead of the front-back-sides-bottom-top armor paradigm, we used one, rapidly-spinning shell as the armor? Keep it thick enough that small munitions won't get through, and let the hull's spinning knock away even perfectly-aimed anti-tank missiles. On the spin tank, in the time it takes the anti-tank missile to prime the plasma, the missile's contact point with the tank hull will have shifted along the perimeter. This means the shaped charges will no longer pointed in the right direction, and will detonate harmlessly, spraying plasma along the hull instead of into it.

Missiles will just roll right off the spin tank.

You might be wondering what kind of rotation speeds are necessary to shed missiles like water. Good question. It depends on a series of factors including but not limited to: projectile mass, projectile velocity, tank hull thickness, tank hull strength, and projectile penetration strength. Unfortunately, I cannot currently simulate this in software, so you'll just have to settle for a hardware implementation!

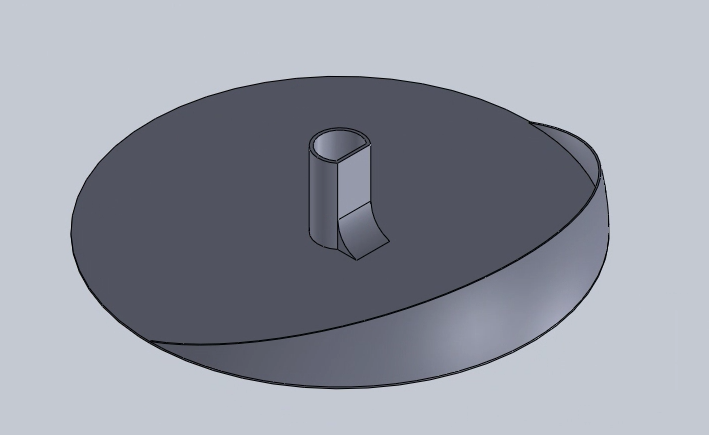

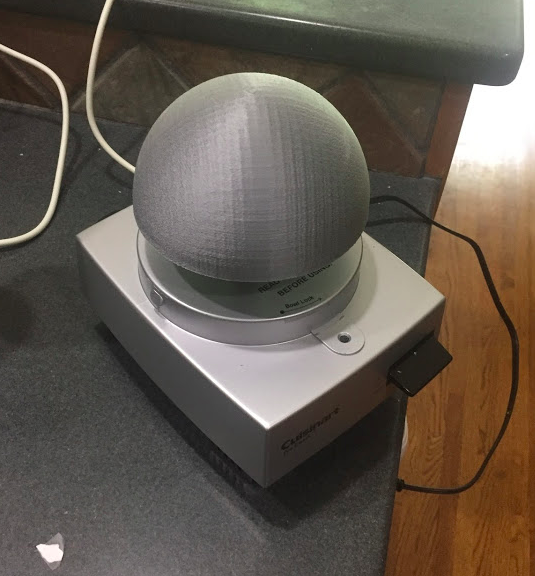

I modeled a quick little dome that fits perfectly on a food processor I have, which spins almost too fast for my phone's built-in slo-mo to capture. Manually counting a mark on the rim, I got about 15 rotations per second. Not bad for a consumer appliance!

I've been using a chopstick in a slingshot to simulate a missile hitting the spin tank. When the dome is stationary, the chopstick has no problem penetrating it. However, the same shot on a spinning dome will leave a dent instead of a hole.

Stationary chopstick firing leaves a hole

Spinning chopstick firing leaves a dent in the hull, but less damage

I need to experiment more with which latitude I'm shooting, since the hull strength changes at different heights. I should also use different lengths and weights of projectiles, since the chopstick is incredibly narrow compared to the dome itself. Some shots on the spinning hull also tore a larger hole than the one on the stationary hull, which I think is caused by a chopstick penetrating the hull followed by the rotation ripping it out.

At the very least, the spin tank reduces the total target size of the same tank, since hitting the edges of the spin tank with a projectile proves to be entirely useless.