The exploration of unexplorable search spaces

Published June 30, 2019

Any hard problem can be solved by randomly guessing — if you're good enough at guessing.

Take my website's aesthetic. The colors composing my website were not chosen at random. I went on a nice site called colourlovers.com where people discover and post colors they think are beautiful and I found a curated selection of the best colors out of the 16.7 million RGB ones. Not only that, they were already matched in a palette of 4 complementary colors! Thank god for these color-space explorers, without them my site would be a garish combination of 4 colors I liked individually, but put together look like an alternative Mardi Gras parade.

[Dream Magnet](https://www.colourlovers.com/palette/482774/dream_magnet) has one of the prettiest cyans I have ever seen

That incident got me thinking. I think it is amazingly frustrating that many problems have solutions that can be guessed. In any field, almost all problems can be randomly, instantaneously solved to a greater extent than methodical approaches are currently solving them. This is because we know what type of thing we're guessing (integers from 1-60), just not what the right guesses are.

In the field of personal finance, I could correctly guess 4 or 5 numbers and win the lottery. The solution space for this one isn't even that big, only 605=777 million (I wonder if the lucky numbers are intentional), but the importance is several orders of magnitude higher than picking a color scheme for my website while only being 1 order of magnitude harder to find.

Or take machine learning for instance. Nowadays, modern research labs spent millions training neural networks with their fancy computers. With the invention of backpropagation by Geoffrey Hinton in 1986, every school and company dropped anything computationally challenging they were working on (re: not webdev or IT) to figure out the fastest way to do matrix math really, really fast. The faster your model could multiply huge matrices of floating-point numbers together, the better/faster/stronger it could tell a dog from a cat or classify a 32x32 pixel image as a airplane, bird, etc.

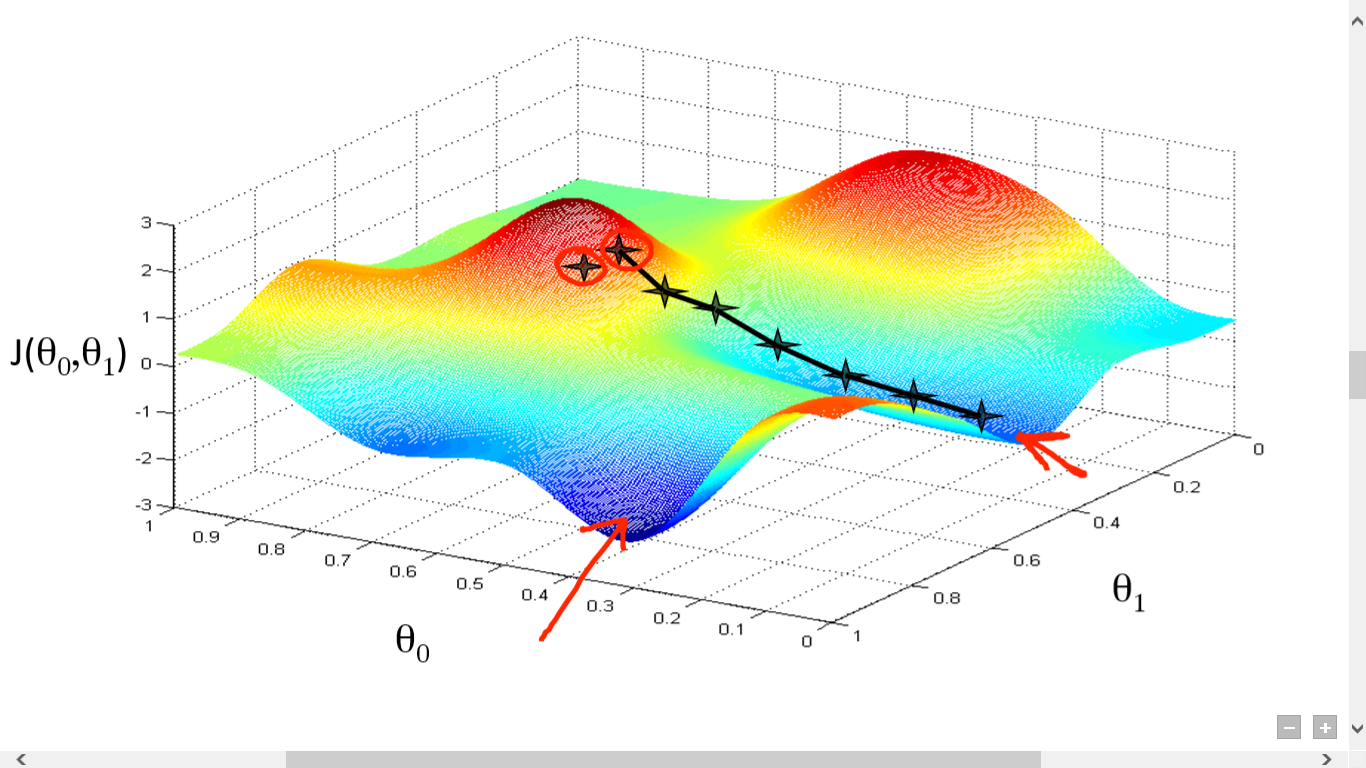

Backpropagation left the machine learning community a method for tuning the matrices. As any high school/college kid interested in machine learning knows, the really hard part of machine learning that Geoffrey Hinton didn't solve is automagically importing data twiddling the matrix numbers to perfection sometime before the heat death of the universe. THAT'S why my neighbor at my first-year college dorm had multiple high-end graphics cards, not to play the Overwatch in 4K at 144Hz while their model is training. My jealousy of their dual 144Hz monitor gaming setup aside, finding the minimum in higher dimensions is HARD.

You think this is bad? Imagine how many bumps it has in the 500th dimension!!

Confronted with all this complexity from today's approach, I could just give up. Like an Amazon warehouse stocking inventory, I could just begin to guess values and randomly shove them into the matrices anywhere they fit. And, in one world out of many I will achieve a miracle: I will find the global minimum by raw chance. Now, there's no academic clout to be gained this way, and I wouldn't know how my matrices worked. But neither does any other ML researcher.

Then take a look at medical research. To find new medicines today, we just add random functional groups to an existing, working drug. To check if doing something random made the medicine more effective somehow, we give it to a bunch of rats, and if it works for them, a bunch of monkeys, and if it works for them, the humans that need it. The process takes millions of dollars and lots of time, and in the end we still don't know how the new drug works until some PhD student figures out the mechanism of action 20 years later.

Why does it matter? It's because I think it's sad that the lives of many experts today will be dedicated to finding the best way to guess at random numbers, with no need to understand how it all works once they've done it.